On Sunday, citizens of Guinea and the Central African Republic (CAR) will go to the polls to elect their presidents for terms of office of seven years.

Both contests could, in theory, go on to run-off ballots. Yet in both, the incumbents are strong favourites, with observers predicting they will clinch victory outright in the first round with more than 50% of the vote.

But that's where the similarities end.

The CAR, vast and landlocked, is one of Africa's poorest countries, marred by chronic instability for decades, with a succession of armed groups motivated by various local grievances and political ambitions.

From 2013 to 2016, only the intervention of African, French, and then UN peacekeepers averted deeper inter-communal violence. The national government in Bangui has often struggled to assert its authority in distant outer regions.

Despite these ongoing challenges, multi-party politics has survived in CAR, along with a notable level of tolerance for opposition and protest. This year has seen significant rebel groups returned to a peace process, disarming and demobilising.

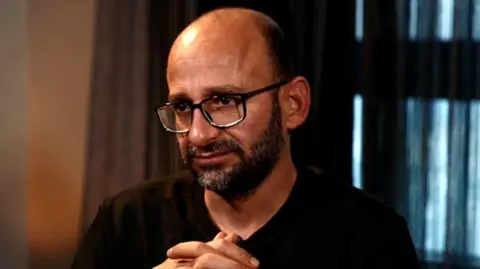

Faustin-Archange Touadéra, a mathematician and former university vice-chancellor, seeks a third term. After entering politics as prime minister, he became a consensual civil-society figure in post-conflict governance, but has since transformed into a more partisan leader, having struck down term limits - a move which has prompted a boycott by parts of the opposition. However, his rival Anicet-Georges Dologuélé remains in the race.

On the other hand, in Guinea, General Mamadi Doumbouya, leader of the September 2021 coup, looks to establish himself as a constitutionally elected ruler. While he faces several challengers, he has overwhelmingly dominated the campaign, and has excluded key opposition figure Cellou Dalein Diallo from the electoral process.

Despite criticism, Doumbouya has maintained good relations with the West, receiving less backlash compared to neighboring regimes. His government is appreciated for progressing toward restoring elected governance, particularly by regional bodies like Ecowas.

While both elections reflect deep-rooted political challenges within their respective countries, they also symbolize hopes for progress and the complexities of post-conflict governance in a dynamic African political landscape.