Chile is perceived by many of its neighbours in the Latin American region as a safer, more stable haven. But inside the country, that perception has unravelled as voters worried about security, immigration and crime chose José Antonio Kast to be their next president.

Kast is a hardline conservative who has praised General Augusto Pinochet, Chile's former right-wing dictator whose US-backed coup ushered in 17 years of military rule marked by torture, disappearances, and censorship. To his critics, Kast's family history, including his German-born father's membership in the Nazi Party and his brother's time as a minister under Pinochet, is unsettling.

However, some of Kast's supporters openly defend Pinochet's rule, arguing that Chile was more peaceful then. In a nod to Chile's past and to accusations levelled at other right-wing leaders in the region after they imposed military crackdowns on organised crime, the 59-year-old pledged in his first speech as president-elect that his promise to lead an 'emergency government' would not mean 'authoritarianism'.

Sunday's election makes Chile the latest country in Latin America to decisively swing from the left to the right, following Argentina, Bolivia, Costa Rica, Ecuador, El Salvador and Panama. Kast's victory places Chile within a growing bloc of conservative governments likely to align with US President Donald Trump, particularly on migration and security.

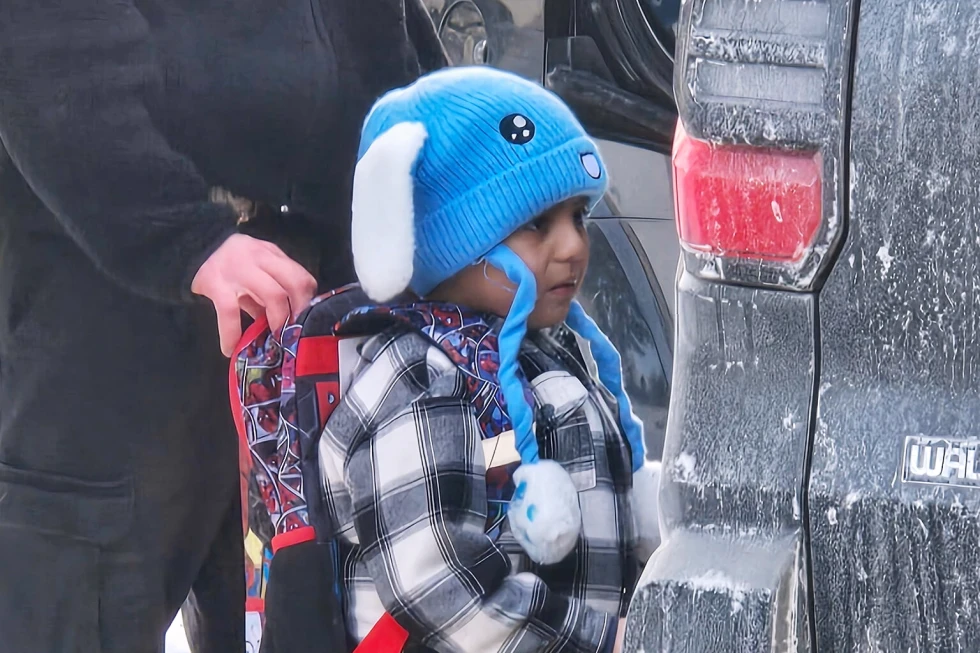

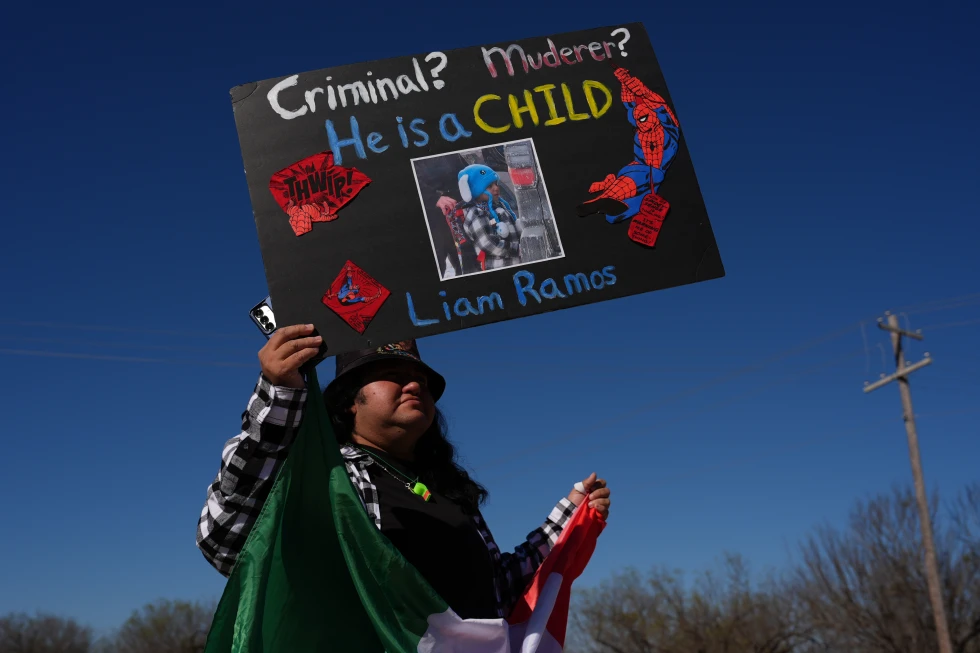

Kast promised a border wall and mass deportations of undocumented migrants. At rallies, he counted down the days until the inauguration and warned that those without papers should leave by then if they wanted the chance to ever return.

His message resonated in a country which has seen a rapid growth in its foreign-born population. Government figures show that by 2023 there were nearly two million non-nationals living in Chile, a 46% increase from 2018. The government estimates about 336,000 undocumented migrants live in Chile, many from Venezuela. The speed of that change has unsettled many Chileans.

Chile was not prepared to receive the wave of immigration it did, says Jeremías Alonso, a Kast supporter who volunteered to mobilise young voters during the campaign. He rejects critics' accusations that Kast's rhetoric amounts to xenophobia.

Kast has blamed rising crime on immigration, an allegation that resonates politically even as the number of murders has fallen since peaking in 2022, and despite some studies suggesting migrants commit fewer crimes on average. Many voters cite organised crime, drug trafficking, thefts and carjackings as contributing towards their sense of insecurity.

For irregular migrants already in Chile, the future feels uncertain. Gabriel Funez, a Venezuelan waiter, fears deportation as Kast's policies unfold.

Carlos Alberto Cossio, a Bolivian national and small business owner, warns that expelling unregistered workers could hurt Chile's economy. Amidst the worries over crime and immigration, Kast's party lacks a majority in Congress, meaning some of his proposals may require compromise and negotiation.