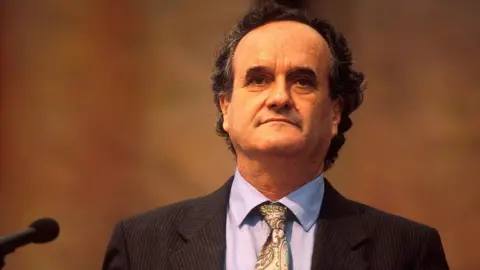

On his Russian TV show, a famous presenter takes aim and unleashes a tirade against the UK.

I'm just glad it's not his finger on the nuclear button.

We still haven't destroyed London or Birmingham, barks Vladimir Solovyov. We haven't wiped all this British scum from the face of the earth. He sounds disappointed.

We haven't kicked out the goddamned BBC with that Steve Rotten-berg. He walks around looking like a defecating squirrel…he's a conscious enemy of our country!

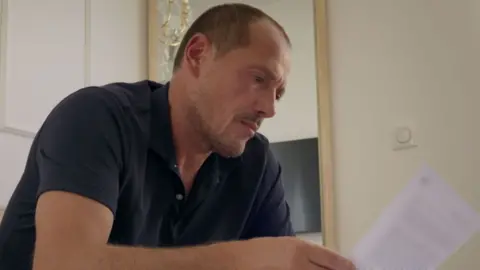

Welcome to my world: the world of a BBC correspondent in Russia. It's a world we offer a glimpse into in Our Man in Moscow. The film for BBC Panorama charts a year in the life of the BBC Moscow bureau, as the Kremlin continues to wage war on Ukraine, tighten the screws at home, and build a relationship with President Trump.

The squirrel barb doesn't bother me. Squirrels are cute. And they have a thick skin - something a foreign correspondent needs here. But enemy of Russia? That hurts.

I have spent more than thirty years living and working in Moscow. As a young man, I fell in love with the language, literature, and music of Russia. At university in Leeds, I ran a choir that performed Russian folk classics. For one concert, I wrote a song in Russian about a snowman who put on so many clothes that he melted.

Like that snowman, the Russia I knew seemed to melt away in February 2022. With its full-scale invasion of Ukraine, the world's largest country had embarked on the darkest of paths. President Putin's special military operation would become the deadliest war in Europe since World War Two.

Looking back, this hadn't come out of nowhere: Russia had annexed Crimea from Ukraine back in 2014; it had already been accused of funding, fuelling, and orchestrating an armed uprising in eastern Ukraine. Relations with the West were becoming increasingly strained. Still, the full-scale invasion was a watershed moment.

In the days that followed, repressive new laws were adopted here to silence dissent and punish criticism of the authorities. BBC platforms were blocked. Suddenly, reporting from Russia felt like walking a tightrope over a legal minefield. The challenge: to report accurately and honestly about what was happening without falling off the highwire.

With Donald Trump back in the White House, Moscow feels that Washington is paying it more respect. Despite the challenges, moments of warmth and curiosity exist amidst the vitriol, and Rosenberg reflects on the complexities of his experiences in Russia, illustrating a dual narrative of resentment and connection.