The silence is pierced by anguished screams as a group desperately searches the earth, uncovering personal artifacts like a watch and a sandal. Such scenes unfold in Sarajevo’s War Theatre during the world premiere of "Flowers of Srebrenica," a play that not only chronicles the tragic events of July 1995 but also highlights the decades of anguish and division that have followed the infamous massacre.

The Srebrenica massacre stands as the darkest chapter in modern European history, where over 8,000 Bosnian men and boys were killed by Bosnian-Serb forces. The United Nations’ claim of protection for the Bosniaks proved illusory, as Dutch soldiers stood by while General Ratko Mladić orchestrated the removal of women and children, leading to an atrocious campaign of killings that remains unresolved and deeply felt.

The play vividly portrays the uncertainty and pain faced by victims' families, many of whom still seek closure decades later, utilizing DNA testing to identify remains buried haphazardly in mass graves. As the cast received acclaim from a supportive audience, contrasting sentiments of denial and division surfaced within Republika Srpska, as political leaders dismiss the events of Srebrenica and stir further discord.

Selma Alispahić, the play's lead actress and former conflict refugee, laments, "I thought that after 30 years we would finally reach an understanding." She elaborates that those who distort the truth only empower the very criminals who thrived during the war.

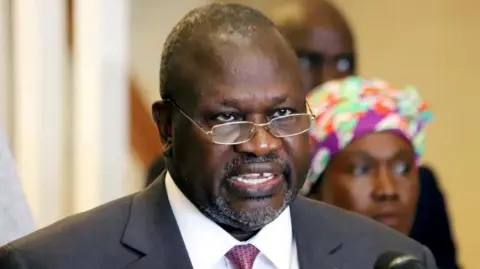

The aftermath of the Dayton Peace Agreement, which established Bosnia and Herzegovina’s present structure by creating ethnic enclaves, has only aggravated tensions. Milorad Dodik, President of Republika Srpska, continues to push divisive legislation, including the establishment of a police force reminiscent of the army's militia from the wartime era. These actions have raised alarms among international overseers who see the need for additional military presence to maintain stability.

In stark contrast to the palpable remembrance within Sarajevo, which embraces the victims through rituals of mourning and solidarity efforts, East Sarajevo exhibits a reluctance to acknowledge Srebrenica's history. Saša Košarac, a senior figure from Republika Srpska, openly challenges the focus on Bosniak suffering and insists on a broader perspective of accountability that includes crimes committed against Serbs during the conflict.

Meanwhile, sentiments of unease grow among Bosniak families who have returned to their ancestral homeland. Mirela Osmanović, who lost two brothers in the massacre and now works at the Srebrenica Memorial Centre, expresses alarm over the upsurge in ethnic tensions, remarking, "It feels like 1992 again."

As political maneuvering continues to stoke divisions, the struggle for acknowledgment and healing remains fraught with challenges, complicating hopes for a reconciliatory future in a land still encumbered by its past.