A small ceremonial fire has been flaming for over 1,300 days on the soil of Wangan and Jagalingou Country in central Queensland, Australia. This fire symbolizes a persistent protest that began over four years ago, rooted in the conflict between the local Indigenous community and the controversial Carmichael coal mine. Operated by Indian energy conglomerate Adani, also known locally as Bravus, this site is seen by many as a threat to the ancestral land of the Wangan and Jagalingou (W&J) people.

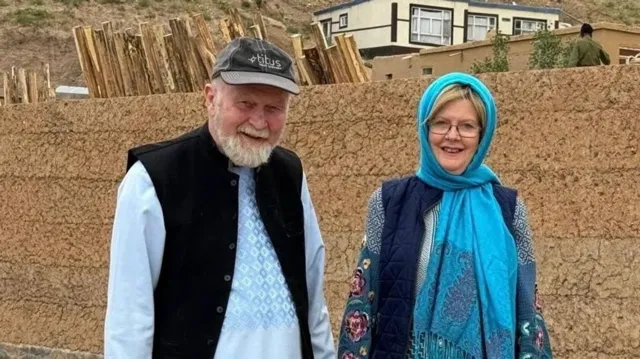

Adrian Burragubba and his son, Coedie McAvoy, have been at the forefront of this resistance, viewing their campaign not just as a legal battle but as a spiritual struggle to ensure cultural survival and protect their historical ties to the land. "Where my land is, there's a mine trying to destroy my country. That country is the roadmap to my history and knowledge about who I am and my ancestors," Adrian states.

Central to their fight is the Doongmabulla Springs, a sacred site linked to deep Aboriginal creation stories, believed to have been formed by the rainbow serpent Mundagudda. These springs are part of a significant underground water system that sustains the arid landscape of the Galilee Basin, recognized as one of the largest untapped coal reserves globally.

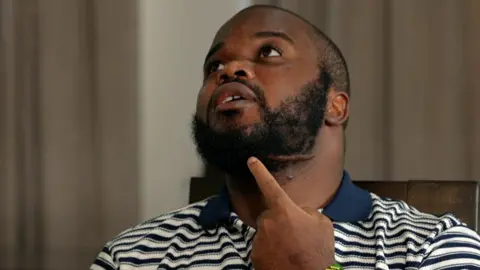

Experts, including hydrogeologist Professor Matthew Currell from Griffith University, warn that mining activities are producing hydrocarbons in spring waters, indicating threats to the ecological integrity of this vital source. His co-authored research published in 2024 has fueled calls for a reevaluation of Adani's groundwater impact models, asserting that unforeseen consequences of mining could endanger the water quality critically tied to the springs.

Despite this evidence, Adani has refuted these claims, branding the researchers as anti-coal advocates. The Australian national science agency, CSIRO, has echoed concerns, concluding that Adani's environmental assessments are inadequate, leading to government action to ban underground mining plans in the area—an action currently being challenged by Adani in court.

The decision to approve Carmichael mine has starkly divided opinions nationwide for nearly a decade. While some in the W&J community signed a land agreement with Adani, enticed by promises of community funding, others argue it jeopardized their cultural integrity and connection to their land. "Mining is God in this country. One mine has divided a whole nation," Coedie contends.

Established laws such as the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (2007) mandate respect for Indigenous rights against intrusions by state projects, though they lack legal enforcement. Australia's long history of suppressing Aboriginal land rights complicates the situation, as the 1993 Native Title Act requires a continuous connection to land for rights to be recognized—an endeavor made challenging by historical removals of Indigenous people from their ancestral homes.

An ongoing judicial battle sees Adrian pursuing a case in Queensland's Supreme Court that relies on human rights protections for Indigenous peoples, arguing that the mine threatens their ability to practice culture and maintain ties to their sacred land and waters. With the outcome of this landmark case still pending, the Burragubba family remains resilient, motivated by their deeply rooted connection to the water. “Without the water, we’re all dead. Without land, we’ve got nothing,” Adrian proclaims, embodying the struggle as both a cultural and existential imperative.