Out on the western Baltic, a coastguard officer radios a nearby, sanctioned oil tanker. Swedish Coastguard calling… Do you consent to answer a few questions for us? Over. Through heavy static, barely audible answers crackle from a crew member, who lists the ship's insurance details, flag state, and last port of call – Suez, Egypt.

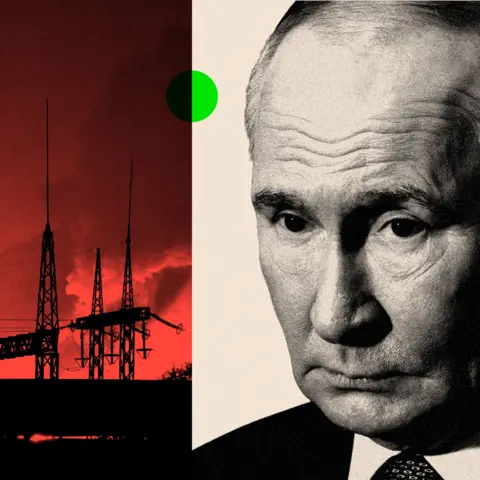

I think this ship will go up to Russia and get oil, says Swedish investigator, Jonatan Tholin. This encounter is just a glimpse into the front line of Europe’s uneasy standoff with Russia's so-called shadow fleet; a term that refers to hundreds of tankers used to circumvent a price cap on Russian oil exports.

Following the Kremlin's full-scale invasion of Ukraine, many Western nations imposed sanctions on Russian energy. Moscow is accused of dodging these restrictions by using aged tankers often obscured by unclear ownership or insurance.

Out at sea, European coastguards are witnessing a troubling trend. Some shadow ships are suspected of not just transporting oil, but also engaging in activities like undersea sabotage and launching illicit drones.

The inability and reluctance of coastal countries to intervene has raised alarms as risks escalate around these vessels. Many of these ships now operate without valid flags, rendering them stateless with ambiguous insurance, leading to concerns about accountability in the event of accidents or disasters.

Data reveals that over 450 falsely flagged ships currently exist due to record sanctions and stricter regulations. This includes the shadow vessel Unity, which has an intricate past involving sanctions and dubious activities.

As the BBC continues to uncover details on vessels like Unity, questions linger about the broader implications of these shadow operations on international maritime law and environmental safety. Despite sanctions and port bans from the UK and EU, Russian oil revenues persist, highlighting the persistent complexity and opacity of the shadow fleet's operations.